Few years changed a country like 1066. That single year gave England a new ruling class, new laws, and eventually a new language. The BBC’s new eight-part drama King and Conqueror tries to capture the speed and shock of that shift, following two rivals on a collision course: Harold Godwinson, England’s last crowned Anglo‑Saxon king, and Duke William of Normandy, the man who would take his crown at Hastings.

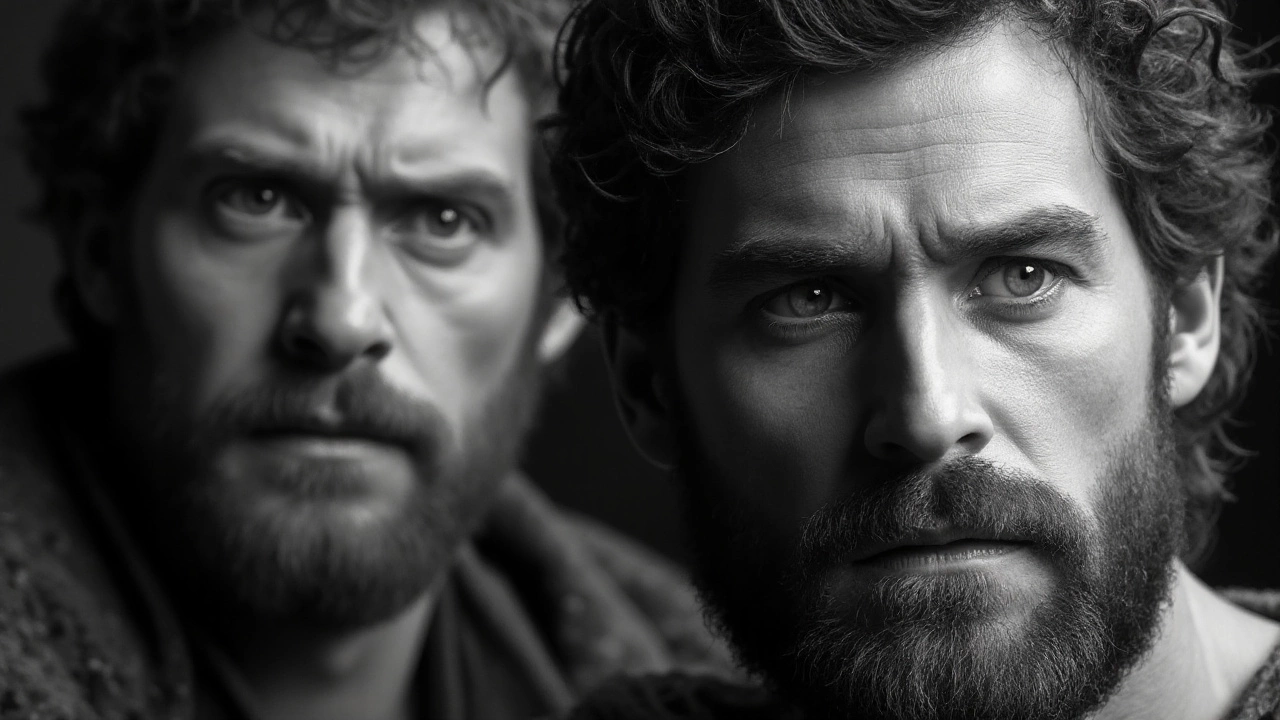

The series casts James Norton as Harold and Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as William, a pairing that leans into charisma and grit over dusty textbook history. Michael Robert Johnson, whose script work on Sherlock Holmes favored pace and punch, writes the show with an eye for knotty politics you can actually follow. The story stretches wider than most 1066 retellings, starting back in 1043 with the coronation of Edward the Confessor and threading through decades of court deals, family feuds, and military gambles.

It’s a tale driven by two households under pressure. In England, Harold rises through a powerful family network, juggling loyalty to Edward, a restless nobility, and a brother, Tostig, who becomes a problem he can’t ignore. Across the Channel, William fights to hold Normandy together while selling a bold claim to the English throne. The show turns their rivalry into a personal and political chess match, knowing full well that no one wrote down their private chats. Yes, there are invented conversations. But the tension feels grounded in the choices both men had to make.

A retelling with modern pacing

BBC historical dramas live or die on clarity. Here the stakes are clean. Edward has no clear heir. Harold has influence and military chops. William believes an oath was sworn in his favor and seeks support to enforce it. The script tackles that web of promises without losing viewers in the paperwork. It’s the kind of approach that can bring new audiences to a period some people think they already know.

The supporting cast helps sell the scale. Emily Beecham plays Edith, Harold’s wife, caught between dynastic duty and personal cost. Clémence Poésy is Matilda, William’s partner in strategy as much as in marriage. Juliet Stevenson’s Lady Emma bridges old and new power. Jean-Marc Barr appears as France’s King Henry, a reminder that Norman politics were never just local. The emphasis on family dynamics keeps the palace scenes sharp, while the war planning grinds forward in the background like an approaching storm.

Visually, the show aims for mud-under-the-nails realism without losing sight of spectacle. Battles lean into shield walls, cavalry impact, and the fatigue of marching, not just the splashy sword swings. Reviewers have praised the urgency and the sense that decisions carry weight, even as some note the practical limits of recreating an 11th‑century world that left fewer traces than later periods. That scarcity puts extra pressure on costumes, sets, and crowd scenes; the series meets that challenge most of the time, if not always.

Expect debates about accuracy. Harold and William are framed as forward-looking leaders, each pushing toward a more centralized, rules-based order—an argument historians still contest. Compressing timelines, simplifying the map of alliances, and polishing motives are all part of the TV bargain. Early reactions suggest the show wins on clarity and momentum, while specialists will circle the details where drama steps ahead of the record.

To ground the action, the series plants anchor points history fans will recognize. Edward’s long reign sets up the succession crisis. Harold’s rapid coronation after Edward’s death tightens the clock. The northern invasion by Norway’s Harald Hardrada, encouraged by Tostig, forces Harold into a brutal sprint: fight at Stamford Bridge, then race south to face William. The Battle of Hastings isn’t treated as a single, sudden blast of violence; it’s the end of a month that pushed men and supply lines past their limits.

For anyone new to this era, a few ideas help frame what’s at stake:

- The English shield wall: a disciplined infantry tactic that could hold if it stayed steady—and falter if it broke to chase.

- Norman cavalry: trained horsemen who relied on repeated charges, feints, and archers to punch gaps in that wall.

- Claims and oaths: whether Harold promised the crown to William—voluntarily or under duress—matters as a moral and political lever.

- Papal backing: the banner sent to William, cited in sources, gave his invasion a religious stamp that helped recruit and fund it.

By the time Hastings arrives, viewers should understand why this wasn’t just a clash of egos. It was a fight over the rules of succession, the reach of the church, and the kind of state that would emerge on the other side. The series doesn’t rewrite the outcome, but it slows the story down enough to show how fragile every step felt in the moment.

History, TV, and the Viking-era boom

The timing is savvy. The show lands while audiences are still hungry for gritty medieval worlds after Vikings, Vikings: Valhalla, and The Last Kingdom. Those series leaned hard into raiding culture and frontier survival; this one shifts the lens to courts and logistics without losing the bite of battle. It’s a difference in flavor, not just setting.

There’s also a neat cultural echo on the horizon: the Bayeux Tapestry is planned to be loaned to the UK in 2026. That 70‑meter embroidered epic is the closest thing we have to a contemporary storyboard of the conquest—ships, banners, mounted charges, and, yes, the famous “arrow in the eye” image that may not be what people think. The series nods to that visual tradition while keeping its drama grounded in character choices rather than iconography.

Critics are split in a predictable way. The show gets credit for humanizing both men—Harold as a capable crisis manager, William as a determined state‑builder—and for giving space to the women who shaped their courts. The pushback focuses on idealization: leaders who seem a bit too self-aware, a pace that sometimes telescopes months into minutes, and battle scenes that, while tense, can’t always match the scale our imaginations demand. That trade-off is common in historical TV, but it will spark talk among history buffs.

Where the series does important work is in showing why the conquest mattered long after the last sword was sheathed. Norman rule brought a fortress-building spree, remapped land ownership, rewired the legal system, and layered French vocabulary onto Old English. If you speak modern English, you speak the legacy of 1066. The drama touches these shifts without turning into a lecture, which is the right balance for prime-time viewers looking for a story first and a seminar second.

There are smart choices to watch for as the season unfolds. Does the show portray Stamford Bridge as the exhausting, pyrrhic win it was for Harold? Do we see the weather delays and logistics that let William land and organize? Are cavalry feints and the collapse of the English line presented as tactics, not just fate? These details matter because they strip away the myth that Hastings was inevitable. It wasn’t.

The cast list hints at that broader canvas. With Jean‑Marc Barr as King Henry of France, the script can sketch how Normandy’s survival shaped William’s temperament before he ever looked across the Channel. With Juliet Stevenson’s Lady Emma—who bridged English and Norman courts two generations earlier—the series can show how dynastic ties quietly primed a later storm. It’s a reminder that conquests don’t erupt from nowhere; they build over decades.

Johnson’s writing keeps the politics readable by treating them like human choices under pressure: who you marry, who you betray, when you risk your army, when you cut a deal. That approach worked in Sherlock Holmes, and it fits here, even as the facts sit 1,000 years away. Viewers meet ambitious people, not museum mannequins. The result is a show that knows its sources and still reaches for emotion.

Expect the usual post‑episode ritual: viewers looking up which scenes are documented and which are stitched for TV. The answer will often be “a bit of both.” We have chronicles, the tapestry, and law codes—useful, but incomplete. We don’t have transcripts of strategy sessions in Winchester or Rouen. That gap is where television steps in, and where this series will keep drawing both praise and nitpicks.

Whether you come for the helmets or the palace intrigue, the BBC has packaged a story that still shapes daily life in England in quiet ways—from surnames and place names to the bones of the legal system. If the show sends people searching for Stamford Bridge on a map, or reading a panel of the tapestry, it’s doing more than filling a Sunday night slot. It’s reopening a case that never quite closed.

Write a comment